Christian Wagner

Feb. 10

Though part of me was hoping for rain, I hiked out from the trailhead under the only blue sky all week. The singletrack bent out from the parking lot and ducked between the grayish-green convalescence of the hilltop grasses—the unmistakable color of February on the few treeless hillsides of the northern Santa Cruz Mountains. It wasn’t long until the trail dipped down into the valley. The whooshes of passing cars on Skyline Blvd was nothing but an oceanic hum through the high redwoods which layered the shrugging shoulders of the western ridge. Before I descended into the heart of the valley and the sky grew dark with the gnarled fingers of bare winter oaks, I paused at the sight of seven or eight raptors circling high to the southeast. My first thought being to get a vantage point and perhaps witness a dive and a kill, I scanned the dark lattice of game trails that webbed the high grassy slopes for a way up the bare hilltop nearest the scene. One of the raptors—coming out of the sun and now recognizable as a Peregrine Falcon (as opposed to the Red-Tailed Hawk I had reflexively assumed)—began a long dive but pulled up before reaching the winter valley canopy. How I wished to be closer to the hunt, having never before seen so many birds of prey zeroing in on such a concentrated area—and for what reason?—but, remembering my injury, it became clear that I would be constrained to more or less the current distance as far as observation went. The hunt was perhaps a mile off in a direct route, probably almost twice that to arrive there on foot. I resolved to leave the scene to my imagination, and proceeded down towards the spindly fingers of the oaks down below, in which the Spanish moss hung like cobwebs while trunks and branches bent and twisted in every manner and direction with the solemn exceptions of the straight and the vertical. It was good to be back out here.

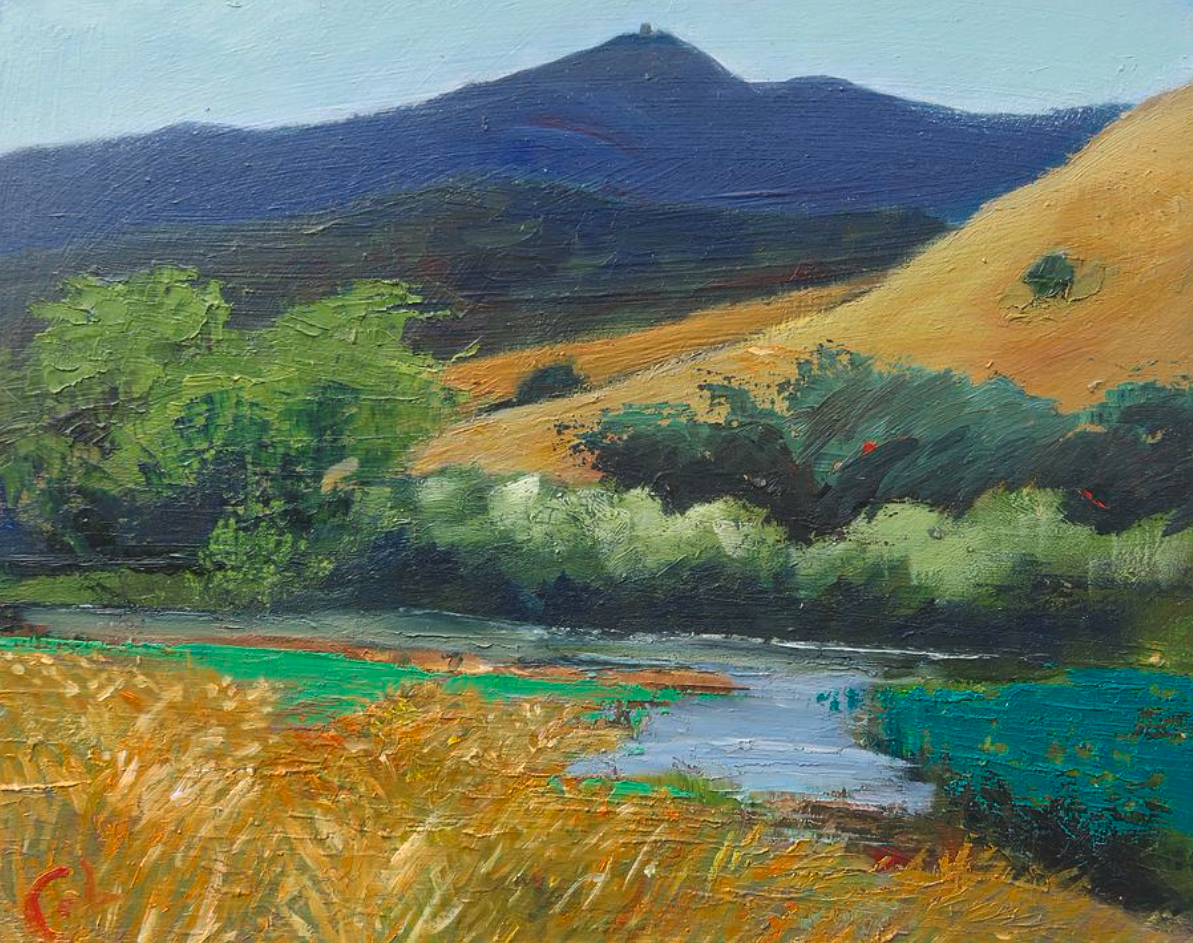

After making a long detour on a particularly well-established game trail which appeared simply too inviting for me to pass up, down through the creek and over a few otherwise inaccessible hilltops—the most striking of which was barren save the ubiquitous gray-green grass and a small live oak with unmossed ivory branches that blossomed out in a perfect cloud. Perhaps in a hundred years or so another hiker might gain that very hilltop and be surrounded by thousands of tons of the huge, sweeping confusion of the mature live oak, so that the hill itself (small as it was) might be almost entirely hidden by the protective wooden elbows that emerged from its crest so long ago—I reached the base of Black Mountain and began the climb up to the high campground. The sun was now somewhat low in the afternoon sky, and it occurred to me to quicken my pace in order to watch the sunset over the ocean above the two main ridges that lay between myself and the sea. There is a unique satisfaction that comes with seeing the flat dark of the ocean from such a distance and such a height, and with the anticipation of that feeling serving as an ample mute over the worries surrounding my old injury, I gained the steep switchbacks free of apprehension.

I sit among a garden of jutting teeth of granite draped with lichen which crowns the flattened summit which outflanks its rolling neighbors. The grass of the unforested hillsides is not found within the bounds of the rock garden, perhaps by the shallowness of the soil. Here there is a different species marked by its low, waxy blades that catch sparks from the distant sunset and thus appear in the cloudless sunset not as living green so much as burning embers. Though the sky is clear from this high seat, I can see that my coastal neighbors must be drowning in a thick fog which appears to blanket the whole Pacific coast to the north and to the south, and—save the of a hardly visible glistening sliver of dark along the precipice of the horizon—would appear to blanket the entire churning expanse all the way to Japan. Even in the valley through which I walked earlier in the day as well as its coastal twin there are great white rivers of fog which have leaked in from the sea, flowing slowly southward, hiding oaks and redwoods under a miasmic shroud save the loftiest fingers and arrowlike spires.

As the reddening sun flattens itself against that dark gleaming sliver beyond the foggy Pacific expanse, I can see around me at intervals the fleeting shadows of a small cohort of tiny mice—no larger than my thumb from head to tail—taking advantage of the dying light to safely emerge from their holes without risking the eager eyes of the falcons, though I suspect gliding owls to begin soon their eventide patrol of these dark heights. One curious individual just darted around a nearby granite stump, very much like the one against which I sit. In a series of quick movements punctuated with brief pauses during which he observes me in complete stillness save the twitching of his nose and ears, the mouse came up nearly to my boots, until fleeing in the blink of an eye at the resuming sound of my pen on this page. I still see his busy shadow intermittently between the boulders, though I doubt he nor any of his comrades will venture any nearer than the ten feet from which I observe, now with some struggle, through the increasing lavender darkness.

The wind has grown icy, and the sun has disappeared though its dim afterglow still paints the western sky. The mice have now been joined by the waltzing music of the bullfrogs in the clear waters of the spring I passed on my way to this summit. A sudden winged palpitation passes quickly overhead and flashes notes of the orange belt of the horizon into my eyes, indicating the incipient nocturnal campaigns of waking bats. My time among these rocky teeth grows short. As I pack up to leave in the waning light, a flash from above catches my eye. A lone streak of smoke carves the sky due west with a single gleaming, meteoric finger, before fading, fading under the diffusing influence of high, fast winds, fading until indistinguishable from the weighty indigo curtain draped down from above.

When I descended the short distance to the high campground, the night had fallen dark and flat around me. Upon entering the designated clearing, I was approached by a polite female ranger, who explained her surprise at seeing the light of a headlamp coming down from the mountain in the dark and requested to see my permit, which I produced from the outer elastic of my pack. As she reviewed the information with a handheld flashlight (she wore no headlamp but a forest green Stetson) I explained to her that I had gotten a late start to the day and had made the decision to enjoy the sunset—which she agreed had been spectacular—and pitch camp in the dark rather than spend those precious natural fireworks driving stakes and tying knots. When she was satisfied with the information on the permit, she handed the slip back to me and the conversation proceeded under the red glow of my headlamp. She instructed me to remain within the boundaries of the clearing until morning so as not to disrupt the nocturnal wildlife, explaining in jest that the designation of “Nature Preserve” was to be taken literally. I apologized for remaining on the hilltop after sundown, though the ranger dismissed my words in good nature, stating once again that it had been quite a spectacular sunset and that she’d have to hand in her badge if she would reprimand any hiker for watching through to its conclusion. After a brief sequence of similar pleasantries, she instructed me to pack out of the campgrounds by the reasonable hour of noon tomorrow at the very latest. I bid her goodnight, to which she returned a farewell and made off toward the fire road, following behind the sweeping white of her flashlight—we did not shake hands due to what she described as “the current state of affairs.” I never learned her name, though I am confident that I could instantly recognize even now her long relaxed voice if I ever heard it again, though her face is a shadow in my memory. Perhaps I would know it under the flat brim of her Stetson, though I cannot be sure.

I pitched my tent in the dark of the campground where two other hikers cooked their dinner over the low hush of a small fierce camp stove, the sound of which they sparsely interrupted with murmured fragments of conversation and the occasional metallic note whenever the tin lid was removed to stir. When the rain fly of my small tent was secured and drawn taught (there was a possibility of rain in the early morning hours) I settled down against a log with my notebook to cook dinner, shielding the flame from the wind by the positioning of my body and lighting my pen and pages under the soft red of my headlamp, though for some time I made no movement of ink for I realized my thoughts had become scrambled in the pitching of my camp. So I waited, with eyes gently closed and feeling within myself for that sensation of coolness that springs from a settled mind, breathing and hearing the babble of boiling of water; so I waited in the dark, in the dark of sky and of mind, so the dark was not only about me but also within me; and so I sat and waited, waited in the dark; in the blind peaceful dark I waited.

It is dark and quiet; I suppose that is what I am here for. If I stifle the sound of my own breath, it is possible to hear the train roaring through Silicon Valley 2,800 feet below me to the northeast. I am glad to be away, though I am not without some bit of guilt at the thought of leaving my mother alone in our home for the night.

I have not been praying enough lately. I could be praying now, but I am not. It is not a question of belief. I know I believe, probably more strongly now than ever before in my short life. Though in the company of other Christians, even those who I know will place no judgement upon me but will only permit the utmost encouragement to pass through their lips, I could make every excuse of preoccupation. However when I am alone up here in this high cold camp, there is no compulsion to efface my own contradictory self under my own inward eyes. Yet still when I search my heart in this dark place, I find resting upon it the weight of deception. Once I was a great fraud though I did not know it—now I am a lesser one, but how clearly I perceive it! The hidden self: the brother, the twin, the coward—how I wish in this moment I had a prayer to pray. I feel I was once able to pray well. Is this a product of linguistic atrophy, a spiritual shift, or is it simply that those flowing prayers that sprung from the Great Fraud’s mouth—those words I thought I had—I really never had to begin with? Could it be that these fumbling prayers are the first genuine ones of my twenty years, and so it is in fact all the better that I lean into this wordlessness, that I look upon this ashen sky with no phrase for my Creator? Silence and awe—this is my prayer tonight.

But God, tomorrow or the next, or someday thereafter, give me words to speak with; give me thoughts to think with. Let me pray courageously. Let me pray like the man I wish I was, the man I hope I will be before I breathe my last breaths over this intricate mesh of Creation. Let me pray like a warrior, why not a preacher? God, let me pray like a Christian.

Feb. 11

My watch failed in the night, so I awoke with the birds. I exited my tent and stepped out into a bright pink winter morning. I was surprised to discover in my camp possibly the largest Giant Salamander I have ever seen, and assumed he must have come up from the spring in the night. At first it merely basked in the new light beside the log against which I had rested the night before, but when I crouched down to get a better look, it embarked upon that slow, constant, blindly perpetual march for which they are famous, which does not cease even when lifted in one’s hands making it necessary to consistently alternate hands like a treadmill in order to prevent them from dropping to the forest floor. For fear of finding him a second time with the heel of my boot in my morning preparations, I lifted him from the dirt and withdrew him to the moist grass at the edge of the clearing where, after a moment’s pause at the change of surface, he continued straight ahead, apparently without heed to direction, in that same determined fashion he had begun back at my camp. The Giant Salamander was not so wet-skinned as I remembered, though this may have simply been a function of spending the night on dry land away from the water.

Returning to evaluate how my tent withstood its first night’s trial, I was pleased to see that it had not at all slackened in the night. However, I deduced that there must have been no small amount of wind running through this clearing as I slept, for two of the stakes had been wedged a few degrees leeward from where I hammered them in though none of the paracord came loose. Perhaps next time I ought to pay closer attention to the wind direction and point the low sloping foot of the tent to the windward, rather than setting it perpendicularly as it was, like the sail of a dingy. Seeing as the sun had not yet breached the hills of the East Bay, I jogged to the nearby summit for a chance to see its first rays as well as to try and discern this day’s destination on the western ridge from this high place. The sunrise did not disappoint, though I could only guess which of the dark seaward forests shrouded the hidden peak of Tabletop Mountain. When I returned to camp to assemble a pack for the day’s journey—a notebook, my remaining liter of water, and a rain layer against the forecast—a zipping noise caught my attention from the other side of the clearing where the couple’s large tent was situated, and I raised my gloved hand to welcome the man who emerged into the day, to which he returned nod and a smile before assembling their stove for breakfast. Suddenly remembering my own spartan packing—only two cups of dry oatmeal and a pinch of salt remained—I decided to forego breakfast and get on hiking on an empty stomach.

My approach took me two miles down the side of the mountain and into the ravine, at which point I descended three miles due southeast all the while with Stevens Creek running past my right shoulder. When I finally crossed the main artery near the base of Tabletop Mountain, I stopped to rest on a creekside log’s living green coverlet for a draught from my diminishing supply (I had left my iodine tablets in the parking lot, so despite the constant presence of the babbling creek it was necessary to make the bottle last). I thought I might have never seen anything greener and more vivacious than the communities along the banks of these low coastal creeks—the wavering ferns which shingle almost every sloping bank, the moss which spreads over nearly every stone and decaying log as well as scales the huge looming oak and redwood trunks and branches in a thick wet blanket as though these green-laden spires were indeed huge sylvan pillars about Nature’s meandering Parthenon; that ubiquitous moss which really is not moss at all but rather millions upon millions of tiny ferns ranging between a centimeter and two inches in length, curled and fog-moistened in their adolescent multitude so as to give a wavy and indiscriminate texture to the neon-shrouded trees and logs—there truly is nothing comparable in all my travels to these most familiar ecosystems which live vibrantly just a few miles from the lights of San José, which are visible from the loftiest heights wherever the redwood forests do not inhibit the view. So many of us scrimp and save for a chance to plunge into the heart of the Amazon or for a voyage among the macrofauna of the Masai Mara, when right in our backyards we have something that rivals their beauty in every respect. Show me an orchid in wide bloom and I will show you the delicate petals of the California Poppy; show me the glistening variegated skin of the poison dart frog and I will show you the golden hide of the Banana Slug; show me one gazelle or impala that can surpass the humble beauty of the watchful Deer that roam these hills; show me one African lion that can rival the elegance and magnanimity of the elusive Mountain Lion, that sleek phantom predator which constantly observes us in stealth, appearing but a mirage on those rare occasions when it divulges to mortal eyes its corporeal secret.

I write from atop the summit of Tabletop Mountain, from which there is no great view save the trees and the birds which swallow this broad peak. Though at the base of the hill I felt a pang in my stomach from lack of fuel, the exertion of the climb came as a welcome distraction and now I perceive no pain at all. Perhaps it will return on the way back.

But I am glad for it all the same. On my way to this lower peak, I stopped often to observe black squirrels as they moved about in the canopy over the ravine. On one occasion I ended up making prolonged eye contact with a keen individual who, after a period of utter still and silence on both sides, suddenly fled into the upper branches, issuing with every leap a series of sneezing-chirping sounds at which immediately my heart was won over to the black squirrel. Though the sound was vaguely familiar to my ears, I regret to admit that I had never once been aware of its source and never even stopped to wonder even what bird or mammal or insect produced such a noise! And for what reason? The noise—funny as it sounded—was immediately echoed by an invisible chorus above and around me, all of whom must have been observing this whole time the standoff between their Countryman and the Biped Stranger. For the rest of my walk, this noise followed me through every twist and turn of the trail up until crossing the clear shallow waters of Stevens Creek and started gaining altitude at Tabletop Mountain. I wonder if all my life this sound has followed me so blatantly through the redwood forests, or if that primary encounter with the curious fellow initiated a chain reaction of messengers all along my path, and was thus a more or less unique occurrence (I have heard of such behavior in crows and songbirds). But either way, though I lament having traveled these forests unawares for so long, I rejoice that I have now heard it! I thank God for the squirrels and the Steller’s Jays and the Giant Salamanders that inhabited the trailsides and who have kept me company this morning.

But seeing as the sun is only getting higher in the sky, and not wanting to miss the Ranger’s appointed noon, I must be shoving off back to camp. It is a rare thing, to have an awakening, a new awareness of something that has always been there but has only just forded the wide stream that stands between the world and the conscious mind. I hope I am ready when the next opportunity arises—I hope I will not be too preoccupied with making time back to camp that I may blind myself to something wonderful that has passed me by. But truly, now, I must be off. What a blessing it is to have feet to walk with; an even greater one to have a world with which to make good use of them.